DR JEKYLL, I PRESUME

There was something strange in my sensations, something indescribably new, and, from its very novelty, incredibly sweet. I felt younger, lighter, happier in body; within I was conscious of a heady recklessness, a current of disordered sensual images running like a mill race in my fancy, a solution of the bonds of obligation, an unknown but not an innocent freedom of the soul: I knew myself, at the first breath of this new life to be more wicked, tenfold more wicked, sold a slave to my original evil; and the thought, in that moment, braced and delighted me like wine...

--Robert Louis Stevenson, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886)

THE most famous literary monster after Dracula and that of Frankenstein is undoubtedly the enigmatic protagonist of Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 novella, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Unlike his Gothic predecessors, however, the pseudonymous ‘Edward Hyde’ was not a physical entity of rotting flesh or Undead blood but a psychological conceit - a creature who literalised previously hidden aspects of the human psyche - which opened him up to almost limitless interpretation in a post-Freudian world which saw him as the first modern ‘monster of the id’.

‘Jekyll and Hyde’ was crafted by Stevenson as a mystery, but the origin of the story is something of a mystery in itself. Edinburgh-born Stevenson had long been fascinated by local legend relating to the case of Deacon William Brodie, a respected 18th-century cabinet-maker and councillor by day but the leader of a gang of burglars by night, who was tried and executed in the city in 1788. In 1884, Stevenson was the celebrated author of Treasure Island and more, and he had co-authored a play on the subject called ‘Deacon Brodie, or a Double Life’, which opened at the Prince’s Theatre in London in July. Stevenson had suffered from ill-health since childhood and required constant medication; he and his wife Fanny had moved to Bournemouth for the sea air, where he had thought to further elaborate the Deacon’s life into a fiction which he titled ‘The Travelling Companion’. But before he could bring the idea to fruition, he was shaken awake from a sedated sleep by a fever dream which seemed to suggest a new variation on the same theme.

Of the half-remembered nightmare, two key incidents stood out: the distraught face of a gentleman seen briefly at a window and the same gentleman, pursued for some unspecified crime, mixing a powder and transforming into another before the startled gaze of the onlookers. Currently bedridden, Stevenson set about capturing the nebulous concept in a three-day frenzy of writing, but his wife (who acted as the custodian of his public image) was appalled at his semi-biographical treatment of the tale and persuaded him to burn the manuscript after suggesting an alternative approach; the first draft of ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ was thus lost to posterity, its content - like the solution to Dickens’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood - a matter only for the speculations of the literati.

Scholars have debated the veracity of this event ever since, but a recently-discovered letter by Fanny appeared to confirm that she burned the draft after showing it to literary critic WH Henley, a friend and confidante of Stevenson’s who served as the model for Long John Silver in Treasure Island. From what else is known about the history of the piece, its genesis can thus be fairly well established:

appeared to confirm that she burned the draft after showing it to literary critic WH Henley, a friend and confidante of Stevenson’s who served as the model for Long John Silver in Treasure Island. From what else is known about the history of the piece, its genesis can thus be fairly well established:

Stevenson had styled the protagonist of ‘The Travelling Companion’ after Deacon Brodie - as a man who was the model of propriety to his peers but who adopted an alias when performing his misdeeds; his original Jekyll was therefore ‘all bad’ with the aptly-named ‘Hyde’ acting as his chemical cover. The story was also set between the respectable parlours and seedy underpinnings of Edinburgh, which Stevenson knew well from a staunch Calvinist upbringing among middle-class burghers and his youthful penchant for carousing in the taverns and brothels of the Old Town. It was this autobiographical inference in the tale that so mortified his wife; Fanny argued that its plea for understanding, rather than censure, of the supposed ‘duality’ in Man’s nature would be better served as an allegory of the struggle in keeping with traditional Christian values, with the added benefit that it removed any association between Jekyll and his creator. In consequence, Stevenson redrafted ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ as a moral fable and set it in London, although he failed to disguise the fact that the mean streets of Soho in the published version remained those of Edinburgh Old Town in his mind’s eye. ‘The Travelling Companion’ and the hurried original draft were subsequently burned, and Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was unveiled to the public as a ‘Shilling Shocker’ in January 1886.

Lawyer Utterson and Richard Enfield are taking the Sunday air, and Enfield tells his companion of an incident he witnessed in which a dwarfish felon knocked over and trampled upon a young girl; he and the girl’s family had taken the man to task and been rewarded with a cheque for £100, drawn on the account of the respectable Dr Henry Jekyll. Utterson is troubled by the tale as Jekyll is a client of long-standing and has just revised his will to favour the same unsavoury individual - one Edward Hyde; he contrives to see Hyde for himself and on doing so, is perplexed to find the doctor in thrall to a repellent character who seems to exude a tangible sense of evil..

Soon after, London is gripped by the brutal murder of the aged MP Sir Danvers Carew, and both a witness to the crime and a broken walking-stick at the scene point unequivocally to Hyde as having been the perpetrator. But the villain has vanished, and Jekyll consequently forswears anything more to do with him. Months pass, during which Jekyll appears to have shrugged off his association with Hyde until, without explanation, he retreats to his rooms and will admit no one. Dr Lanyon, a mutual friend, is taken ill and dies - but not before leaving Utterson a sealed missive. During a second stroll with Enfield, Utterson spots Jekyll seated at his study window; inquiring after his health, the two are shocked to see him suddenly convulsed by some strange malady. Jekyll’s manservant Poole confides in Utterson his fears for his master’s safety and the lawyer is persuaded to break into Jekyll’s rooms; when he does so, he finds the doctor dead, a phial of poison by his side..

Utterson now unseals Lanyon’s letter, which tells of Hyde having sought his help in obtaining a mix of chemicals. Lanyon obliged but, curiosity aroused, he forced the man at gunpoint to down the concoction in his presence. Hyde did as he was bid and, before Lanyon’s horrified gaze, the killer of Carew transformed into the upstanding personage of Henry Jekyll! It was this revelation which had brought about Lanyon’s illness and early death.

Jekyll has also left a confession, which now reveals all:

In the course of his studies to separate out the evil in man by chemical means, he had happened upon a potion which foregrounded the very thing he had been trying to subdue; this younger, livelier, less developed version of himself he had called Hyde. Fascinated by his discovery, he at first revelled in the ability to cast off the shackles of society as it suited him, safe in the knowledge that at length he could return to the physical shelter of Jekyll - until the day came when a stronger and more assertive Hyde began to resurge in him involuntarily, and the murder of Carew was the result. By then, he had exhausted his supply of the potion, which led him to seek Lanyon’s help. It subsequently transpired that one of the components had been impure and he was no longer able to duplicate the formula and contain the fiend within..

One course of action remained open to him while he still retained his grip on Jekyll - Hyde would meet justice by his own hand...

It should be clear from the above that Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is some remove from the later interpretations of it in drama. Within six months, the novella had sold more than 40,000 copies and so popular had it become that it could no longer be seen as a mystery; to the contrary, what attracted its readership was the perceived ‘message’ in the tale - that giving in to the temptations of the flesh was the road to perdition. The notion was seized upon by newspaper editorial and sermon alike, and the tale of Jekyll and Hyde became a touchstone for a growing number of social reformers who had begun to rail against the inequities of the late Victorian age.

Being a Scot, the ‘devil’ with whom Stevenson’s fictional doctor metaphorically communed was the liberating bravado of drink, not libido - an element of the piece that was singularly misunderstood by its English critics, blind-sided as they were by the strictures of Victorian ‘family values’: Hyde was the imp let out of a bottle, not out of the britches. The appropriation of the story by moral crusaders brought its own problems for Stevenson, however; an atheist to boot, he was uncomfortable with the preaching that was an integral part of allegory, preferring readers to draw their own conclusions from the actions of his characters. But he had taken Fanny’s advice and instead of it being read as a plea for accommodation of the baser instincts of Man in some form other than suppression and denial - the Establishment weapons of the day - the tale was taken to advocate them To make matters worse, the ‘secret life’ of Jekyll was widely regarded as one of sexual license, whereas Stevenson had intended the doctor’s deceit to be a critique of hypocrisy and the feigned respectability of the new middle class (the only woman in ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ is Hyde’s drab Soho landlady), as he made clear in a response to the clergy’s use of the tale in sermonising: ‘The harm was in Jekyll because he was a hypocrite, not because he was fond of women,’ he wrote. ‘But people are so full of folly and inverted lust, that they can think of nothing but sexuality. The hypocrite let out the beast Hyde - who is no more sensual than another, but who is the essence of cruelty and malice, and selfishness and cowardice: and these are the diabolic in man - not this poor wish to have a woman, that they make such a cry about.’

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was the subconscious outcome of Stevenson wrestling with his Presbyterian conscience, intellectual atheism notwithstanding; he was only too aware of the ‘sinner’ in his own psyche and the Dr Jekyll of the novella is already living a double life before the transformative potion even features, pursuing good works by day and ‘plunged in shame’ by night as he confesses in his ‘Full Statement of the Case’ - a fact that commentators on the tale tend to neglect. ‘Man is not truly one but truly two,’ he surmises, and his idea with the experiment is to separate the two sides of his nature so that they can function independently, without either acting as an anchor on the other - not to suppress the ‘evil’ in favour of the good. As the concept was essentially nonsensical, in the same way that some of Stevenson’s peers thought a criminal tendency could be detected in facial physiognomy, the practicalities of such an arrangement are not worked through, but the dream imagery of the tale carries it forward in the imaginary vein of HG Wells’s later The Invisible Man or The Time Machine and narrative dynamic is achieved by the gradual usurping of the good by the evil, once it has been afforded free rein. Stevenson’s purpose was to invite philosophical debate, at a time when science was beginning to address all manner of social and societal issues, but the forces of reaction saw the story differently, and Jekyll’s potion was itself transformed into a mirror to the ills that many thought were corrupting Victorian England and which needed to be stamped out with authoritarian zeal.

In each of us, two natures are at war - the good and the evil

--intertitle, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1920)

The first stage adaptation of Jekyll and Hyde was by Thomas Russell Sullivan and designed for the American actor Richard Mansfield. This being contemporaneous with the publication of the novella, the mystery of Hyde’s identity could be retained and the only changes over its three acts were a compression of events and the addition of a fiancée for Jekyll. ‘Anything more loathsome than his face has never been seen on the stage,’ was the judgement on Mansfield’s Hyde that was levied by the critic of the St James’s Gazette when the play opened at the Lyceum Theatre in London in February 1886. But the intrusion of a (platonic) romantic relationship into the schema cast Jekyll’s addiction to the potion in a different light, and with the mystery redundant, the subsequent film versions concentrated their firepower on the less obtuse account of the doctor’s descent into depravity that comprises the last chapter of the novella.

Some half-dozen ‘shorts’ of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde were produced between 1908 and 1913, but the page of a supposed medical text that opened the 1912 version with James Cruze - ‘The taking of certain drugs can separate Man into two beings, one representing evil and the other good’ - set the tone for all future adaptations. ‘A ghastly extravaganza, with a marvellous transformation scene,’ Punch magazine had recorded of the story’s Lyceum outing, and Hollywood’s preference for linear narrative saw Jekyll’s experiment with the potion brought formally to the fore. With it, his change into Hyde became the sine qua non of the tale and the intrigue of his mysterious affinity with a criminal reprobate slipped silently into the background: Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was now as much of a science fiction as it had been a slice of Gothic soul-searching.

Richard Mansfield’s metamorphosis from Jekyll into Hyde had caused a sensation on the stage but early screen versions chose to use primitive camera dissolves to achieve the same result, rather than the lighting trickery and pre-applied greasepaints which had been Mansfield’s secret weapons. Cruze turned Hyde into a leering, fang-toothed goblin, doubled over and prancing about in madcap Keystone fashion, but King Baggot, the following year, reduced him to an even more comedic caricature who crouched and slouched and pulled silly faces. Not until 1920 did a worthwhile adaptation arrive, when Paramount cast ‘Great Profile’ John Barrymore in the title roles, with Martha Mansfield (no relation) as the recalcitrant doctor’s now-obligatory fiancée and Nita Naldi (‘Gina - who faced her world alone’, as the caption-card decorously addresses her) as the object of his illicit passion.

The film’s emphasis on the good-vs-evil aspect of the story meant that much screen-time was given over to Jekyll’s philanthropic pursuits and charity work, so as to make unequivocal the contrast between the saintly doctor and his evil alter ego. But screenwriter Clara Berenger’s reading of the text has Jekyll so saintly that his descent into depravity became improbable without persuasion, and a borrowing from Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray was necessitated in the form of a worldly-wise mentor - in this case Sir George Carewe (Brandon Hurst), who is nominated to lead Jekyll astray. ‘The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it,’ Carewe urges, and the formerly upright doctor is soon embarked on a night-life of (presumed) debauchery in consequence. (The pious overtone in director John Robertson’s version of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is cloying in the extreme, but such was the influence of the church on the new medium of the motion picture in its formative phase.)

The depiction of Victorian London in the 1880s that was created for the film above the Amsterdam Opera House in New York (where Barrymore was performing by day in Richard III) is as much at odds with authenticity as the tale’s direction of travel - Bow Street Runners are despatched to bring Hyde to heel when the Metropolitan Police had been patrolling the streets for more than half a century - but all the historical inconsistencies paled into insignificance with the coup de théâtre that Barrymore pulled off twenty-seven minutes in, when Jekyll finally drinks the potion to inaugurate a screen archetype that would live in countless films thereafter. Instead of becoming ‘smaller, slighter and younger’, as per the novella, he gains in stature, adding hairy talons, a domed crown, a swarthy complexion and a saturnine demeanour to the mix. The Hyde of the movies was born, and it was not that of Stevenson but of medical monstrousness and theatric sensation. (Barrymore did as Mansfield had, performing the initial throes of the change to camera before submitting to a cut that enabled the appending of makeup appliances.) The makers of the 1920 version correctly assumed that for Hyde to conduct his nocturnal business with some plausibility, his features could not be too outlandish; Barrymore’s Hyde looks devious and devilish, but he remains presentable as a ‘client’ to bar-owners and brothel-keepers alike. In the context of the films, this is something that both the 1920 and 1941 adaptations got right, and the Oscar-winning 1932 take on the story got very, very wrong. (Although released in 1932, Paramount actually premiered Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde on Christmas Eve 1931 to qualify it for the new Academy Awrads.)

Instead of his life as Hyde being in the form of the young, sprightly, ‘livelier image of the spirit’ that Stevenson devised, Barrymore’s Hyde is an ugly, hunchbacked degenerate, which is hardly what Jekyll might have desired from his potion - especially in the context of wishing to attract the opposite sex. But Berenger’s purpose was to portray Hyde’s hedonism as morally depraved, his sins echoed in the flesh, in another conscious lift from Dorian Gray.

Instead of his life as Hyde being in the form of the young, sprightly, ‘livelier image of the spirit’ that Stevenson devised, Barrymore’s Hyde is an ugly, hunchbacked degenerate, which is hardly what Jekyll might have desired from his potion - especially in the context of wishing to attract the opposite sex. But Berenger’s purpose was to portray Hyde’s hedonism as morally depraved, his sins echoed in the flesh, in another conscious lift from Dorian Gray.

The one incident drawn directly from the story was the trampling of the child, which is utilised later in the scenario as a prelude to Lanyon and Carewe becoming suspicious of Jekyll’s connection to Hyde, but the revelation of the two being one is conducted in front of Carewe, rather than Lanyon, so as not to leave the film without a sympathetic figure at its close. This final transformation is the high point of the Barrymore version: Jekyll appears to grow taller still, features distorted and eyes positively glowing with malice and hate, as he berates Carewe for leading him into temptation before battering the man to death with his own cane. Robertson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde may not have been faithful as an adaptation of a classic, but it was indisputably the birth of the horror film proper.

Fearful of turning into Hyde once more with his fiancée beckoning him at the door, Jekyll swallows the poison and expires in anticlimax. But the point had been made and sensation had won the day; from here on in, audiences would expect to see Jekyll turn into Hyde as frighteningly as special effects might allow, and all sense of social comment in the tale would be lost to literary history - though another dozen years were to pass before Hyde reared his hideous head onscreen again.

One of the consistencies that each succeeding screen version of Jekyll and Hyde inherited from the novella was the notion that Jekyll’s laboratory adjunct opened out onto a dingy London slum. This was true to a degree of the Edinburgh of Stevenson’s day - a city of two distinct halves, of ‘public probity and private vice’, where the wynds and ways of the medieval old town abutted onto the respectable facades of Georgian town-houses - but that was not the case in London and the Jekyll of the story lives close to Regent’s Park, where he experiences the first involuntary transformation. Stevenson’s alternative hang-out of choice for Hyde was Soho, but Soho would have been a cab-ride away - yet it features in the films as mere streets distant, no further from the refuge of the antidote than can be surmounted by a run. A man of Jekyll’s professional standing (servants in tow) would have resided in Mayfair or Belgravia, with Soho closer by, but its adjacent Hyde Park could not be used by Stevenson due to the name association and Regent’s Park was substituted, the switch in the geography of the tale upended in consequence.

The Regent’s Park incident had not featured in the Barrymore film, where it was substituted by a dream sequence with Hyde in the form of a spider, but it would play a key role in the subsequent sound versions, the first of which was directed by Rouben Mamoulian and starred Fredric March. The sudden popularity of ‘horror’ films in the early 1930s, initiated by Universal’s Frankenstein and then Dracula (both 1931), had encouraged other majors to follow suit and Paramount had chosen to remake Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde as part of its contribution to the burgeoning new genre. With the emphasis now on visual horror, Stevenson’s metaphysical muse was made over as a full-blown monster yarn, with no fewer than six onscreen transformations from Jekyll into Hyde (or vice versa) placing the focus of the story firmly on the bestial and further still from the intellectual discourse that its author had sought to inspire.

What you are about to see is a secret you are sworn not to reveal. Now.. you who have sneered at the miracles of science. You, who have denied the power of Man to look into his own soul.. You, who have derided your superiors… Look-!

--Edward Hyde (Fredric March), Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1932)

With the advent of sound narrowing the psychological gap between viewer and viewed, Mamoulian thought to make things more immediate still by opening Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde with a sequence shot in the first-person - Jekyll is introduced via his hands plying the keys of an organ; he is seen fleetingly in a mirror as he leaves home for the lecture-hall; our first full sight of him is at the lectern, the audience for his thesis becoming the same as that for the film itself. This was clever cinematic sleight-of-hand, and it seemed to mesh with a tale that had a more cerebral foundation for its horrors than had been the case with those of Twenties’ pioneer of the grotesque, Lon Chaney.

Mamoulian thought to make things more immediate still by opening Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde with a sequence shot in the first-person - Jekyll is introduced via his hands plying the keys of an organ; he is seen fleetingly in a mirror as he leaves home for the lecture-hall; our first full sight of him is at the lectern, the audience for his thesis becoming the same as that for the film itself. This was clever cinematic sleight-of-hand, and it seemed to mesh with a tale that had a more cerebral foundation for its horrors than had been the case with those of Twenties’ pioneer of the grotesque, Lon Chaney.

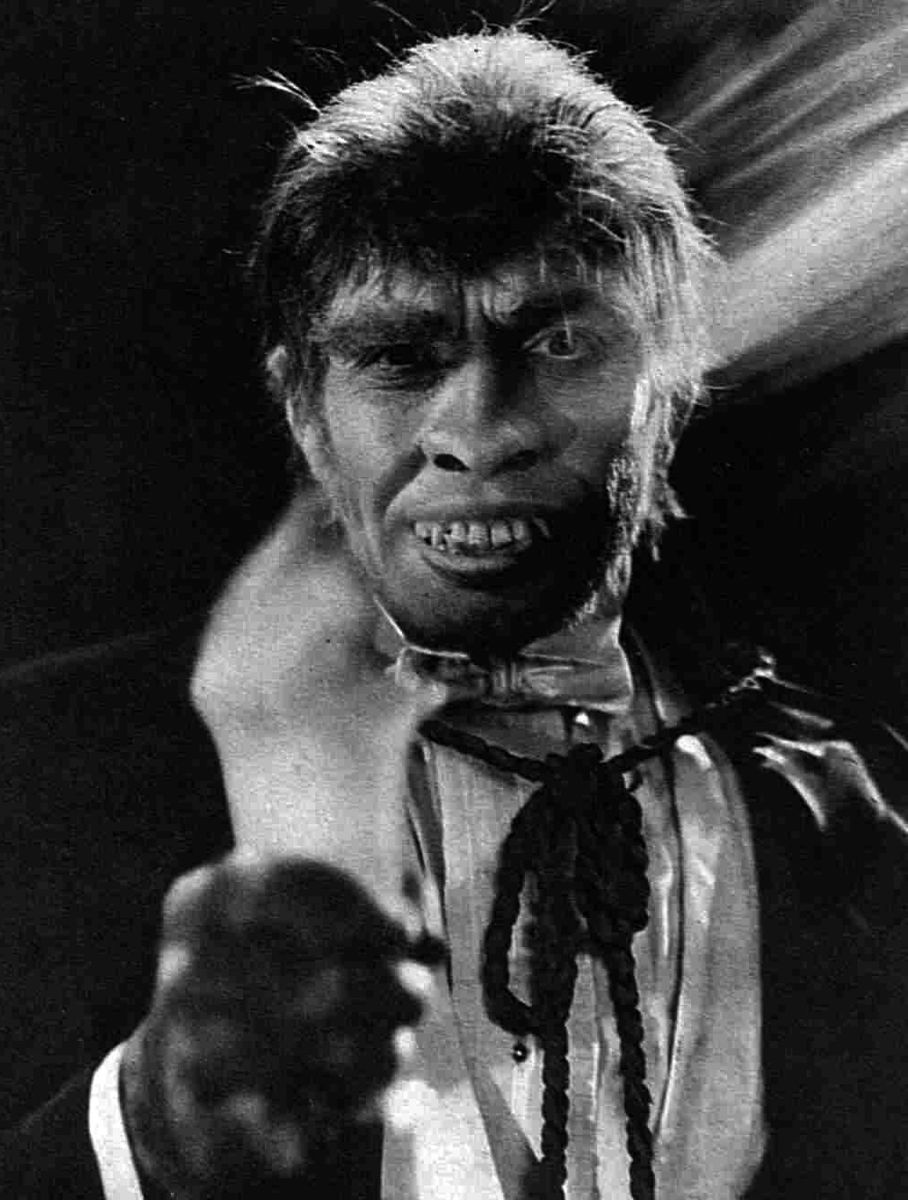

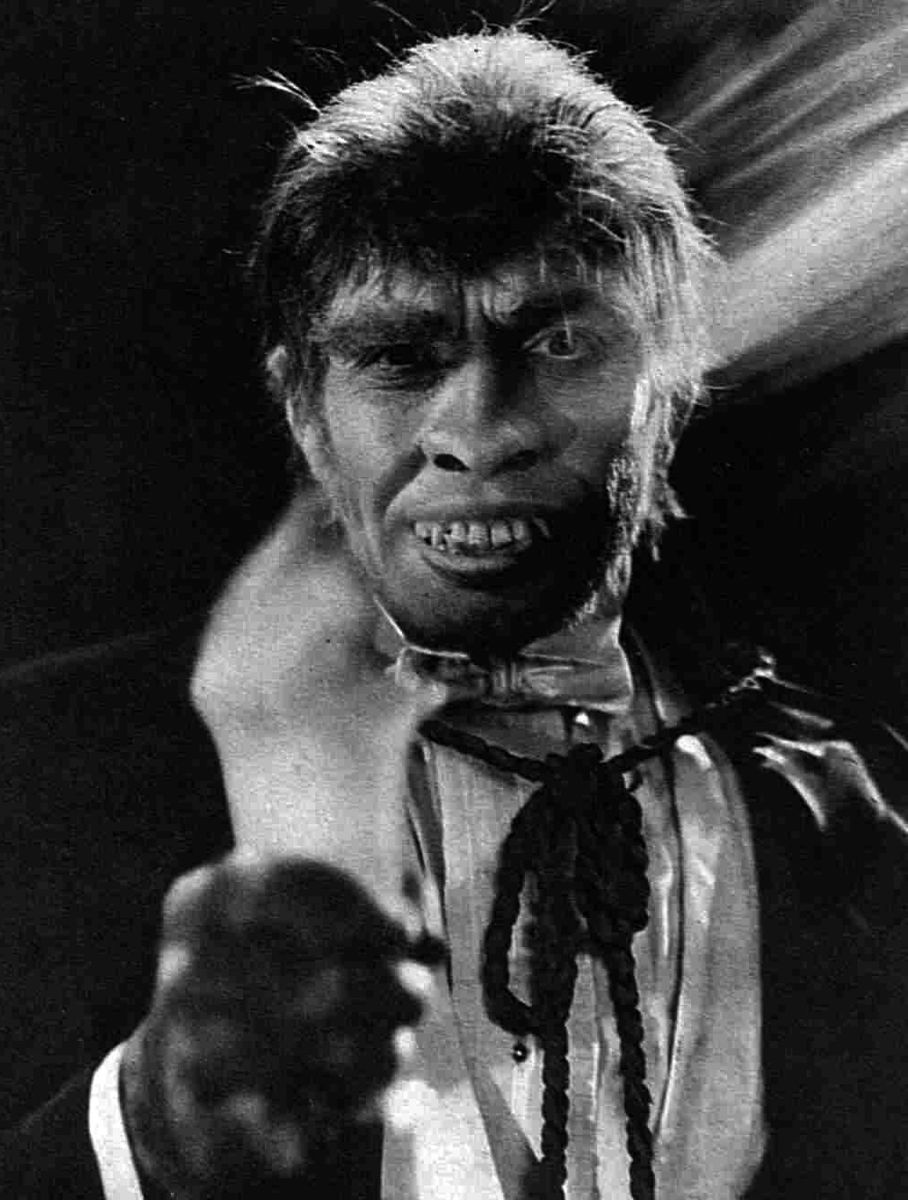

The film began life as an unashamed remake of the same studio’s 1920 version; March’s Hyde was initially kitted out with a makeup that aped that of Barrymore before Mamoulian opted for a look based on Neanderthal Man, and the incident of Hyde trampling the child, which the first film had included to alert Carew to the connection between Jekyll and Hyde, was also shot but edited out when it no longer fulfilled that role in Samuel Hoffenstein’s revised script. Hoffenstein nevertheless nailed his colours to the same devotional mast as its predecessor by having Jekyll tell his students - as a man of ‘science’, no less - that his current research is into the soul.

In order to best contrast Hyde’s licentiousness with the reserve of Victorian society in general, also dropped was the notion of Carew as tempter of Eden; in Halliwell Hobbes’s characterisation, he is both the protector of his daughter’s virtue and a preserver of moral convention - the antithesis of his previous self. It is Carew’s strict adherence to propriety that persuades March’s Jekyll to the potion, not a wish to corrupt the good doctor. ‘Can a man dying of thirst forget water?’ Jekyll inquires rhetorically of Lanyon (Holmes Herbert), its pre-Code inference unmistakeable in context. Jekyll’s first change into Hyde is aborted due to an interruption by Poole, but his sexual frustration eventually gets the better of him - a pot boils over symbolically on the fire and a second, more permanent change puts him with Ivy (Muriel Hopkins), the tart whose seductive teasing has induced him to imbibe the transformative potion, whom he swiftly entices with a promise of trinkets. ‘How am I to get it?’ she asks; ‘How do you think you’re going to get it?’ he replies, leering in lustful anticipation.

As with Jekyll, our first sight of Hyde has come in a mirror and in keeping with the story, the March incarnation was designed to be younger and slighter in stature than Jekyll, but with the physiognomy and stereotypically cropped hair of the Victorian criminal class. There similarity ends, however. Rather than one eager to taste of forbidden fruit, March’s Hyde determines to take it by force: Ivy is brutalised into submission, and the overarching effect is of Jekyll as a latent psychopath, instead of an inquisitive scientist interested in exploring the mysteries of the psyche.

While more authentic in dress, Mamoulian’s film supplied the same curious depiction of London. It sensibly makes no mention of period, so the Dickensian decor (its art direction having drawn inspiration from Gustave Dore’s 1872 collection, London, a Pilgrimage) could well be construed as correct - but it is still not the London of Stevenson’s day. Were Jekyll in the simian guise of March’s Hyde to have strode the streets of the capital in the 1880s, he would likely have been shot on sight, not be the recipient of the odd glance or in a position to rent a clandestine bolt-hole for his mistress. March’s make-up was rightly impressive - the two personae do appear to be completely different people - but Hyde is indisputably a monster and his ability to gadabout London uncontested flew in the face of a genre logic which already decreed that a face like his would have elicited screams of terror in other such films. Not here, though; his first encounter with Ivy merely produces a shudder of disgust in Hopkins, as though the populace of the metropolis had somehow been infused with a modern liberal conscience.

The story is returned to again when Jekyll involuntarily succumbs to the effects of the elixir: ‘Thou wast not born for death, immortal bird...’ he muses, quoting Keats, as he spots a nightingale in the park. An unlikely cat pounces on the unsuspecting bird and the message is delivered figuratively once more: Jekyll is overcome by a Hyde determined to enact the ultimate sin, and the murders of Ivy and Carew follow in short order: ‘You wanted him to love you, didn’t you?’ he inquires of the cowering Ivy, before throttling her in her boudoir. A counterpoint to the brutality has already been inserted into the narrative with Jekyll praying to God for forgiveness, but only as a sop to the censors: moral equivocation wins the day - the murder scenes are staged with relish; the devotional one as sanctimonious necessity. For all its technical and artistic prowess, Mamoulian’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was unabashedly exploitational. In consequence, it became one of the most successful films of its year.

The story is returned to again when Jekyll involuntarily succumbs to the effects of the elixir: ‘Thou wast not born for death, immortal bird...’ he muses, quoting Keats, as he spots a nightingale in the park. An unlikely cat pounces on the unsuspecting bird and the message is delivered figuratively once more: Jekyll is overcome by a Hyde determined to enact the ultimate sin, and the murders of Ivy and Carew follow in short order: ‘You wanted him to love you, didn’t you?’ he inquires of the cowering Ivy, before throttling her in her boudoir. A counterpoint to the brutality has already been inserted into the narrative with Jekyll praying to God for forgiveness, but only as a sop to the censors: moral equivocation wins the day - the murder scenes are staged with relish; the devotional one as sanctimonious necessity. For all its technical and artistic prowess, Mamoulian’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was unabashedly exploitational. In consequence, it became one of the most successful films of its year.

By this time, the ending of the Barrymore film was considered too tame and a full-on onslaught by Lanyon and a contingent of police provided a more rousing finale as Hyde is cornered in the laboratory. Mamoulian evidently felt that a sixth and final transition, before the startled eyes of the pursuers, might try his audience’s patience a little far; a clumsy series of lap-dissolves over still images accomplishes the task at speed and Hyde is shot to death as he prepares to leap upon Lanyon, knife in hand. The cursory nature of this parting effect was not enough to dampen critical enthusiasm for those which preceded it, however, and Mamoulian refused to divulge their secret, though it was not difficult to fathom that filter-dependent, pre-applied make-ups were utilised to realise the illusion and the trick was repeated on Nils Asther in Paramount’s The Man in Half Moon Street (1945). The accolades showered on March, and the novelty of the full-on transformations, blinded reviewers to both the adaptive iniquities of the film and its cavalier detour into monstrousness - most of those who were wowed by Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde were simply won over by the spectacle of it.

‘Fredric March is the stellar performer in this blood-curdling shadow venture. His makeup as Hyde is not done by halves, for virtually every imaginable possibility is taken advantage of to make this creature “reflecting the lower elements of Dr Jekyll’s soul” thoroughly hideous...’ So wrote New York Times critic Mordaunt Hall. Trade paper Variety was no less impressed: ‘March does an outstanding bit of theatrical acting. His Hyde make-up is a triumph of realised nightmare.’ With plaudits like these, it is small wonder that Fredric March won the Best Actor Oscar for 1931.

What’s this? - Whose face is this? That’s not my cheek - and yet it is. That’s not my mouth, and yet there’s something there that’s like my mouth. How strange.. my eyes.. Can this be evil, then? The man is shunned and scorned and hidden deep inside him, that since the start of time has been the cause of misery and shame. Shame? Misery? - I feel no shame; I feel no misery. This evil has been maligned.. This evil is a pleasant thing... This evil is a fine thing!

--Edward Hyde (Spencer Tracy), Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1941)

When M-G-M decided to mount a new version of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde nine years later, no such pantomimic variation on Villeneuve’s Beauty and the Beast as enacted by March was considered viable for the sophisticated mainstream audiences of the day, and the fairy-tale fantasy of Universal’s The Wolf Man had vacated the A-feature stage for the backwaters of the B movie. The world, if not yet the US, was now at war, and a more sombre outlook on life was feeding imperceptibly into the output of Hollywood’s dream factories. Love and loss, as exemplified by 1939’s conflict-themed Gone With the Wind, were the keys to current box-office success, and Stevenson’s novella was itself transformed from a moral allegory with little romantic interest into a tragic love story. With that aspect to the fore, the studio cast two of its hottest contract properties alongside an actress borrowed from producer David O Selznick in what was planned to be one of its most prestigious projects of the year.

At the time, none were higher on the A-list than double Oscar-winner (Captains Courageous and Boy’s Town) Spencer Tracy, who was seen by some as an odd choice to play Stevenson’s Faustian medico but whose ability to ‘open’ a film was unquestionable. Patricia Morison auditioned for the role of Jekyll’s fiancée Bea Emery and Susan Hayward for that of Ivy Peterson, but both parts went eventually to others: 20-year-old ‘bad girl’ Lana Turner as the former and Swedish sensation Ingrid Bergman (whom Selznick had under contract) as the latter. The film was to have been produced by British-born Metro executive Victor Saville, but Saville blotted his copybook by campaigning clandestinely for America to join Britain in its fight against the Nazis so the hard-nosed Victor Fleming (whose credits included The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind) was allotted the task in his place.

At the time, none were higher on the A-list than double Oscar-winner (Captains Courageous and Boy’s Town) Spencer Tracy, who was seen by some as an odd choice to play Stevenson’s Faustian medico but whose ability to ‘open’ a film was unquestionable. Patricia Morison auditioned for the role of Jekyll’s fiancée Bea Emery and Susan Hayward for that of Ivy Peterson, but both parts went eventually to others: 20-year-old ‘bad girl’ Lana Turner as the former and Swedish sensation Ingrid Bergman (whom Selznick had under contract) as the latter. The film was to have been produced by British-born Metro executive Victor Saville, but Saville blotted his copybook by campaigning clandestinely for America to join Britain in its fight against the Nazis so the hard-nosed Victor Fleming (whose credits included The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind) was allotted the task in his place.

During the 1940s, Freudian theory would take hold of Hollywood in a big way, a notable example of which was to be Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945, also with Bergman). This obsession with psychoanalysis would reach its zenith in the noir cycle of the post-war years, but M-G-M screenwriter John Lee Mahin was among the first to tap into this new source of story material, and he used it to shift the story from a simple allegory of good and evil to a more contemporary reading of suppressed sexual desire. For what was effectively to become a Gothic noir, Mahin was aided by stricter censorship than Mamoulian had to contend with in his pre-Code version, which meant that subtler means had to be deployed to indicate the erotic nature of Jekyll’s obsession.

Hollywood’s Victorians of the 1940s were closer to the real thing than anything before; London, like Paris, was at the height of modernity and while swathes of the East End were ashamedly a slum, the city as a whole was a beacon to Empire and a far architectural cry from the Dickensian half-world depicted in Mamoulian’s film. Tracy’s Hyde installs his Ivy in an elegant apartment, as he would have in life - in the Haymarket or Piccadilly; he talks of going to (the) Albert Hall, and the route to his garçonnière crosses a park of electric lighting and wrought-iron railings. Both films offer up the same sexual predilection for their Hydes, however, that of le vice anglais: flagellation. Hopkins’s Ivy was matter-of-fact in 1932 about how Hyde abused her - ‘It’s a whip,’ she notes of the wheals on her back - but Bergman was allowed only to expose her (unseen) injuries to Jekyll in the remake, Tracy’s reaction revealing the nature of her trysts with Hyde. March could toy suggestively with Ivy’s garter prior to a fleeting glimpse of a nude Hopkins slipping between the sheets in her Soho bedroom; Mahin and Fleming had to be more circumspect, and they contrived Freudian dream-montages to mask the transformations into Hyde, whose symbolism was such that the MPAA’s Breen office still demanded they be shorn of their more blatant imagery.

The complaint most often levelled at the film is over Tracy’s lack of a suitable make-up as Hyde. The literary Hyde is occasionally described as ‘ape-like’, but in reference to his manner and impetuosity; his features are given no clear characteristic beyond a ‘displeasing smile’ and the notional stamp of ‘Satan’s signature’. Tracy’s Hyde is true to the novella in both respects and, while his face may reveal little of the make-up man’s art, it clearly does not look like that of Jekyll. Jack Dawn’s subtle magic altered Tracy’s bone-structure, mouth and the bridge of the nose; it slicked down his hair into a rakish mane worthy of Sir Philip Green, and it gave his famously benign countenance a saturnine streak that was more chilling in close-up than the lecherous leer of March’s evolutionary throwback. If Fredric March was a troglodyte in an opera-cape, Spencer Tracy was a satyr in a lounge suit.

The complaint most often levelled at the film is over Tracy’s lack of a suitable make-up as Hyde. The literary Hyde is occasionally described as ‘ape-like’, but in reference to his manner and impetuosity; his features are given no clear characteristic beyond a ‘displeasing smile’ and the notional stamp of ‘Satan’s signature’. Tracy’s Hyde is true to the novella in both respects and, while his face may reveal little of the make-up man’s art, it clearly does not look like that of Jekyll. Jack Dawn’s subtle magic altered Tracy’s bone-structure, mouth and the bridge of the nose; it slicked down his hair into a rakish mane worthy of Sir Philip Green, and it gave his famously benign countenance a saturnine streak that was more chilling in close-up than the lecherous leer of March’s evolutionary throwback. If Fredric March was a troglodyte in an opera-cape, Spencer Tracy was a satyr in a lounge suit.

Despite being made under the strictures of the Production Code, the sensual aspect of the film is far more intense than the music hall bawd of its predecessor; Hyde’s initial encounter with Ivy in the Palace of Frivolities fairly crackles with unspoken longing, his sibilant overtures and unflinching stare making all too clear the sexual nature of his intent towards the guileless barmaid. And Mahin’s script gifts Hyde with some eloquent flights of lyrical fancy as he cuts a swathe through Victorian society: when asked by Ivy where he is taking her, he replies, ‘Tonight, I follow the rainbow’ - an allusion to Fleming’s direction of The Wizard of Oz. ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about,’ she pleads, but he is unrelenting, adding with sinister and rapacious insinuation, ‘She doesn’t know what I’m talking about.. But you’ll find out... You’ll find out.’ When his race with Ivy is run, his poetic bent is given fuller flower: ‘Dance - dance and dream,’ he choruses, as he strangles her. ‘Dream that you’re Mrs Henry Jekyll of Harley Street, dancing with your own butler and six footmen. Dream that they’ve all turned into white mice and crawled into an eternal pumpkin’ - a eulogy fit for one of the great villains of the screen, and a more exhilarating epitaph than Hyde offered to Ivy in the same scene in 1932: ‘I’ll give you a lover now. His name is Death.’

John Lee Mahin’s screenplay was ahead of its time: the film that it sired belonged more to the era of Psycho and Cape Fear than it did to a day when the names of Jekyll and Hyde were equated to Universal monsters like the Dracula or the Wolf Man. Due to its star-power, it was a successful venture for Metro, but critics damned it by defaulting to onerous comparisons with its brash predecessor. Victor Fleming’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was no more faithful to Stevenson than the film which preceded it, both owing their allegiance to Thomas Russell Sullivan, John Barrymore and the Hollywood conventions of sin and redemption. But as an exercise in psychopathology, which is what most adaptations of the tale become, it ranks head-and-shoulders above them all. A director and actors at the peak of their powers, supported by the best in every department that a major studio could muster.

The disturbing thing about Golden Age Hollywood’s venal interpretation of Stevenson’s story is the degree to which the analogy is taken. The studio system had long considered actors merely as ‘cattle’ (to quote Hitchcock); actresses even worse. In both sound versions of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the doctor’s monstrous id is not depicted simply as unbridled lust but as sexual sadism; it was not enough to seduce Ivy and set her up as a secret mistress in concert with the popular notion of Victorian double standards - she had also to become the victim of mental and physical abuse, bordering on torture. And in both films, Hyde’s violence is restricted to Ivy - the murder of Carew comes about only when his fatherly concern is an impediment to Hyde’s desire to mete out the same treatment to Jekyll’s fiancée. In Mamoulian’s film, Jekyll is transformed not just into a libidinous rake but a rampant misogynist: his repressed desire is to terrorise, subjugate and rape. From the perspective of the #MeToo sensibilities of today, this can be seen as reflecting a prevalent attitude among the male-dominated Hollywood establishment of the time - but if nothing else, it was now some way from anything that the author of the story ever intended.

By the 1950s, Hollywood studios felt that Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was a spent force. The preceding three decades had all produced large-scale versions of Stevenson’s novella featuring some of the greatest stars of their day, but the tale was now too commonplace, too much a part of the cultural landscape for yet another rendition. Abbott and Costello had used it as a foil for slapstick, B movies such as Son of Dr Jekyll (1951) and Daughter of Dr Jekyll (1957) had annexed its plot to their own, and even the new fad for science fiction was inclined to add man-into-monster transformations to the likes of Monster on the Campus (1958) without so much as a by-your-leave to the story that started it all. Radio and television had over-familiarised things further still, with the likes of Dennis Price starring in a two-part version for ITV during its inaugural year of 1956, and the cod-Freudian observation of someone being a ‘Jekyll-and-Hyde’ had long since become a colloquialism.

Not until the end of the decade was interest in Stevenson’s original revived - by Hammer in the UK, which had been propelled by the success of The Curse of Frankenstein into a remake programme of all the classics from the Golden Age of Hollywood horror, and by the great Jean Renoir in France, who had been looking for a property for television to get his venerated teeth into. Both responded simultaneously to the lure of unbridled anarchy at a time when a new permissiveness onscreen had invited a resurgence of horror subjects, and both turned with fresh eyes to Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

Renoir’s Le Testament du Docteur Cordelier was released theatrically in the UK as Experiment in Evil, complete with obligatory ‘X’ certificate, and cast Jean-Louis Barrault of Marcel Carné’s immortal Les Enfants du Paradis (1942) in the twin roles of Dr Cordelier and the sprite-like but psychotic Opale. Renoir’s variant paradoxically thought to disguise its origin by going back to the text and revealing the monstrous connection between the two only at the climax of the film, whereas fast-forwarding the twist to the second reel by means of a transformation scene had now become de rigueur for anyone thinking about an adaptation of the tale; in this respect, and in Barrault’s impish and sociopathic performance as Opale, Le Testament du Docteur Cordelier came closer than any other screen version (its vérité setting of modern-day Paris notwithstanding) to keeping the faith with Stevenson.

Hammer went in the opposite direction, with eminent playwright Wolf Mankowitz ‘interpreting’ the story instead of adapting it. The Hyde of The Two Faces of Dr Jekyll (1961) was consequently made over as a young, virile, man-about-town, whose predilections are directed towards exposing the hypocrisy in those around him. This high-minded reading captured the spirit of Stevenson, but it ignored the horrific element of the story which audiences had come to expect; the transformation of an ageing scientist into a younger version of himself was unlikely to have inspired many thrills, so it was sidelined in favour of a ménage à trois and an intellectual polemic that left viewers cold. The film was a flop on both sides of the Atlantic, and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde went back into deep freeze for another ten years until producer Milton Subotsky decided to embark on a new version with British horror ‘icon’ Christopher Lee - finally - in the famous dual role.

I, Monster was to have been shot in 3-D, via an arduous process devised by Subotsky that involved set-ups which supposedly created an optical illusion. The idea was abandoned within a week of shooting when the desired effect failed to materialise, though a residue of the tortuous compositions remains in the film: the camera tracks self-consciously past prominent objects in the foreground. When I, Monster was beaten into production by Hammer spin-off Dr Jekyll and Sister Hyde, the names of the characters were changed to Marlow and Blake and inspiration was credited to ‘a story’ by Robert Louis Stevenson. Director Stephen Weeks’s version of ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ stretched to barely 75 minutes on the screen - an impoverishment which had not been seen since Universal’s potboilers of the Forties. As such, the film was rated a second-feature on release. In contemplating ‘Jekyll and Hyde’, filmmakers could usually rely upon ever more horrific depictions of Jekyll’s alter ego if all else failed but, even there, I, Monster proved to be the exception: Lee’s first transformation is conveyed by a slight dishevelling of his otherwise trim toupee; he then sprouts goofy teeth and grows a bulbous nose - a make-up, credited to Harry Frampton, that sank Hyde’s screen persona to a new low.

‘I’m working with a very special patient - a man who can only visit me at night...’

--Dr Henry Jekyll (Anthony Perkins), Edge of Sanity (1989)

After that, ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ continued its downward trajectory on the screen. Edward Hyde became just another in the cinema’s rich pantheon of monsters, able to metamorphose into whatever form suited the prevalent neurosis. He had been transgendered in Dr Jekyll and Sister Hyde, but he was quickly re-equipped with a prominent phallus by Walerian Borowczyk in the uncut version of Docteur Jekyll et les femmes (1981) and Spain’s Paul Naschy appended him to his own parodic catalogue of serial monsters, alongside the wolf man, the vampire and Jack the Ripper. This real Victorian villain enjoyed something of a revival of interest in the late Eighties, which enabled producer Harry Alan Towers and French porn director Gérard Kikoïne to combine the two and turn Hyde into a dope-fiend and Ripper-style stalker in Edge of Sanity (1989); to make unequivocal his composite’s murderous credentials, Kikoïne cast Psycho legend Anthony Perkins in the title-role(s), so the character of Hyde was not only conjoined with that of ‘Saucy Jack’ but Norman Bates as well. The British-Hungarian co-production was little more than a soft-core sex film with pretensions - a plot-less parade of peek-a-boo imagery, its action confined to brothels, bagnios and bars, elegantly photographed but devoid of wit or style.

The last outing of note for Dr Jekyll and his alchemical doppelganger came in Mary Reilly (1996), Stephen Frears’s big-budget adaptation of Valerie Martin’s 1990 novel, which attempted to refresh the piece by telling it from the point-of-view of a maid in the doctor’s household. Aside from the novelty of setting the action in its original location of Edinburgh, the result was ponderous and uneventful and not helped by a version of Hyde which required of actor John Malkovich only that he sport a bohemian wig - nonetheless managing somehow to remain unrecognisable to Jekyll’s domestic staff. By this time, CGI had exerted its seductive embrace on even worthy filmmakers and the last act transformation had Hyde in the form of an homunculus, sprouting fully-formed out of Jekyll’s shoulder like the ape-twin in 1961’s The Manster. Further attempts at the novella in relatively unvarnished form have cropped up from time to time on television, starring the likes of Jack Palance, Michael Caine and David Hemmings, but if ever a story in the form that films decreed for it had passed its sell-by date, Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous discourse on the ‘duality’ of Man is that story.

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was a groundbreaking work in many respects. Stevenson referred to his creation, Hyde, as a ‘Gothic gnome’, but the premise of the tale foreshadowed the science fiction self-experimentation of the likes of Wells’s The Invisible Man, the mystery element predated that of many of Conan Doyle’s ‘Chinese Box’ Sherlock Holmes puzzles, and its dialectic on human weakness and the frailties of the flesh paved the way for Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray , on which it wielded considerable influence.

The reductive requirements of the Victorian stage had abridged this to the simple Judaeo-Christian battle between good and evil, in keeping with the moral tenets of the day. Hollywood had then discarded all residual complexity and used ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ as a DeMillesian opportunity to have its exploitation cake and eat it - pushing the boundaries of sexual license on screen while at the same time condemning it with tub-thumping evangelism. The result was the birth of one of the great ‘monster’ archetypes and the story’s influence on all aspects of the fantasy genre is without peer or measure. But it has come at the cost of a proper appreciation for one of true masterworks in the Literature of Terror.

appeared to confirm that she burned the draft after showing it to literary critic WH Henley, a friend and confidante of Stevenson’s who served as the model for Long John Silver in Treasure Island. From what else is known about the history of the piece, its genesis can thus be fairly well established:

appeared to confirm that she burned the draft after showing it to literary critic WH Henley, a friend and confidante of Stevenson’s who served as the model for Long John Silver in Treasure Island. From what else is known about the history of the piece, its genesis can thus be fairly well established: Instead of his life as Hyde being in the form of the young, sprightly, ‘livelier image of the spirit’ that Stevenson devised, Barrymore’s Hyde is an ugly, hunchbacked degenerate, which is hardly what Jekyll might have desired from his potion - especially in the context of wishing to attract the opposite sex. But Berenger’s purpose was to portray Hyde’s hedonism as morally depraved, his sins echoed in the flesh, in another conscious lift from Dorian Gray.

Instead of his life as Hyde being in the form of the young, sprightly, ‘livelier image of the spirit’ that Stevenson devised, Barrymore’s Hyde is an ugly, hunchbacked degenerate, which is hardly what Jekyll might have desired from his potion - especially in the context of wishing to attract the opposite sex. But Berenger’s purpose was to portray Hyde’s hedonism as morally depraved, his sins echoed in the flesh, in another conscious lift from Dorian Gray. Mamoulian thought to make things more immediate still by opening Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde with a sequence shot in the first-person - Jekyll is introduced via his hands plying the keys of an organ; he is seen fleetingly in a mirror as he leaves home for the lecture-hall; our first full sight of him is at the lectern, the audience for his thesis becoming the same as that for the film itself. This was clever cinematic sleight-of-hand, and it seemed to mesh with a tale that had a more cerebral foundation for its horrors than had been the case with those of Twenties’ pioneer of the grotesque, Lon Chaney.

Mamoulian thought to make things more immediate still by opening Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde with a sequence shot in the first-person - Jekyll is introduced via his hands plying the keys of an organ; he is seen fleetingly in a mirror as he leaves home for the lecture-hall; our first full sight of him is at the lectern, the audience for his thesis becoming the same as that for the film itself. This was clever cinematic sleight-of-hand, and it seemed to mesh with a tale that had a more cerebral foundation for its horrors than had been the case with those of Twenties’ pioneer of the grotesque, Lon Chaney. The story is returned to again when Jekyll involuntarily succumbs to the effects of the elixir: ‘Thou wast not born for death, immortal bird...’ he muses, quoting Keats, as he spots a nightingale in the park. An unlikely cat pounces on the unsuspecting bird and the message is delivered figuratively once more: Jekyll is overcome by a Hyde determined to enact the ultimate sin, and the murders of Ivy and Carew follow in short order: ‘You wanted him to love you, didn’t you?’ he inquires of the cowering Ivy, before throttling her in her boudoir. A counterpoint to the brutality has already been inserted into the narrative with Jekyll praying to God for forgiveness, but only as a sop to the censors: moral equivocation wins the day - the murder scenes are staged with relish; the devotional one as sanctimonious necessity. For all its technical and artistic prowess, Mamoulian’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was unabashedly exploitational. In consequence, it became one of the most successful films of its year.

The story is returned to again when Jekyll involuntarily succumbs to the effects of the elixir: ‘Thou wast not born for death, immortal bird...’ he muses, quoting Keats, as he spots a nightingale in the park. An unlikely cat pounces on the unsuspecting bird and the message is delivered figuratively once more: Jekyll is overcome by a Hyde determined to enact the ultimate sin, and the murders of Ivy and Carew follow in short order: ‘You wanted him to love you, didn’t you?’ he inquires of the cowering Ivy, before throttling her in her boudoir. A counterpoint to the brutality has already been inserted into the narrative with Jekyll praying to God for forgiveness, but only as a sop to the censors: moral equivocation wins the day - the murder scenes are staged with relish; the devotional one as sanctimonious necessity. For all its technical and artistic prowess, Mamoulian’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was unabashedly exploitational. In consequence, it became one of the most successful films of its year. At the time, none were higher on the A-list than double Oscar-winner (Captains Courageous and Boy’s Town) Spencer Tracy, who was seen by some as an odd choice to play Stevenson’s Faustian medico but whose ability to ‘open’ a film was unquestionable. Patricia Morison auditioned for the role of Jekyll’s fiancée Bea Emery and Susan Hayward for that of Ivy Peterson, but both parts went eventually to others: 20-year-old ‘bad girl’ Lana Turner as the former and Swedish sensation Ingrid Bergman (whom Selznick had under contract) as the latter. The film was to have been produced by British-born Metro executive Victor Saville, but Saville blotted his copybook by campaigning clandestinely for America to join Britain in its fight against the Nazis so the hard-nosed Victor Fleming (whose credits included The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind) was allotted the task in his place.

At the time, none were higher on the A-list than double Oscar-winner (Captains Courageous and Boy’s Town) Spencer Tracy, who was seen by some as an odd choice to play Stevenson’s Faustian medico but whose ability to ‘open’ a film was unquestionable. Patricia Morison auditioned for the role of Jekyll’s fiancée Bea Emery and Susan Hayward for that of Ivy Peterson, but both parts went eventually to others: 20-year-old ‘bad girl’ Lana Turner as the former and Swedish sensation Ingrid Bergman (whom Selznick had under contract) as the latter. The film was to have been produced by British-born Metro executive Victor Saville, but Saville blotted his copybook by campaigning clandestinely for America to join Britain in its fight against the Nazis so the hard-nosed Victor Fleming (whose credits included The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind) was allotted the task in his place.  The complaint most often levelled at the film is over Tracy’s lack of a suitable make-up as Hyde. The literary Hyde is occasionally described as ‘ape-like’, but in reference to his manner and impetuosity; his features are given no clear characteristic beyond a ‘displeasing smile’ and the notional stamp of ‘Satan’s signature’. Tracy’s Hyde is true to the novella in both respects and, while his face may reveal little of the make-up man’s art, it clearly does not look like that of Jekyll. Jack Dawn’s subtle magic altered Tracy’s bone-structure, mouth and the bridge of the nose; it slicked down his hair into a rakish mane worthy of Sir Philip Green, and it gave his famously benign countenance a saturnine streak that was more chilling in close-up than the lecherous leer of March’s evolutionary throwback. If Fredric March was a troglodyte in an opera-cape, Spencer Tracy was a satyr in a lounge suit.

The complaint most often levelled at the film is over Tracy’s lack of a suitable make-up as Hyde. The literary Hyde is occasionally described as ‘ape-like’, but in reference to his manner and impetuosity; his features are given no clear characteristic beyond a ‘displeasing smile’ and the notional stamp of ‘Satan’s signature’. Tracy’s Hyde is true to the novella in both respects and, while his face may reveal little of the make-up man’s art, it clearly does not look like that of Jekyll. Jack Dawn’s subtle magic altered Tracy’s bone-structure, mouth and the bridge of the nose; it slicked down his hair into a rakish mane worthy of Sir Philip Green, and it gave his famously benign countenance a saturnine streak that was more chilling in close-up than the lecherous leer of March’s evolutionary throwback. If Fredric March was a troglodyte in an opera-cape, Spencer Tracy was a satyr in a lounge suit.